How the plugin maps the WordPress data model into the GraphQL schema

This is how Gato GraphQL has mapped the WordPress data model into a corresponding GraphQL schema.

The WordPress data model

WordPress has the following entities:

- posts

- pages

- custom posts

- media elements

- users

- user roles

- tags

- categories

- comments

- blocks

- meta properties

- others (options, plugins, themes, etc)

These entities can have a hierarchy. For instance, post, page and media elements are both custom post types, and tags and categories are both taxonomies.

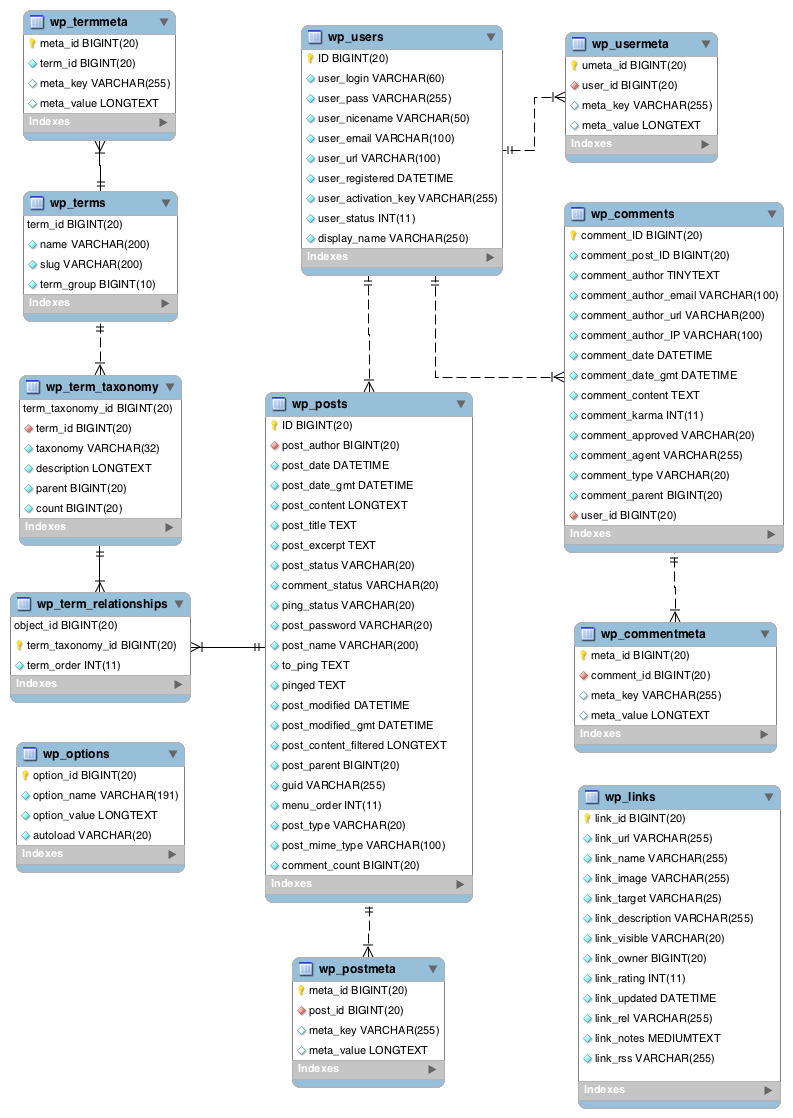

This is the WordPress database diagram, showing how data for all entities is stored:

Is the mapping an exact replica of the DB diagram?

When mapping the WordPress database into a GraphQL schema, is the same diagrame above respected 1 to 1?

No, it is not. While the database diagram is an actual implementation, GraphQL is an interface to access the data from the client. These two are related, but they can be different. GraphQL doesn't care about the database: it doesn't think in SQL commands, or know there are database tables called wp_posts and wp_users.

So we don't need to worry too much about the database diagram when creating the GraphQL schema for WordPress. Even more, we can produce a GraphQL schema that fixes some of the technical debt from the WordPress data model.

Mapping the WordPress data model as a GraphQL schema

Let's do the mapping. First, we map the original entities as types, as much as possible. From the list of entities in the WordPress data model, we produce the following types for the GraphQL schema:

PostPageMediaUserUserRolePostTagPostCategoryComment

Then, we add all the expected fields to every type. To represent the schema, we can use the SDL, or Schema Definition Language. (This is used for documentation purposes only; the plugin itself does not use SDL to codify the schema: it's all PHP code).

These are the fields (among many others) for a Post:

type Post {

id: ID!

title: String

content: String

excerpt: String

date: Date!

}These are the fields (among many others) for a User:

type User {

id: ID!

name: String

email: String!

}We also create the corresponding connections, which are fields that return another entity (instead of a scalar, such as a number or a string). For instance, we represent a post having an author, and a user owning posts:

type Post {

author: User!

}

type User {

posts: [Post]

}Fields and connections can also accept arguments. For instance, we enable Post.dateStr to be formatted, and User.posts to filter entries, limit their number and sort them:

type Post {

dateStr(format: String): Date!

}

type User {

posts(

filter: RootPostsFilterInput

pagination: PostPaginationInput

sort: CustomPostSortInput

): [Post!]!

}

input RootPostsFilterInput {

authorIDs: [ID!]

authorSlug: String

categoryIDs: [ID!]

dateQuery: [DateQueryInput!]

excludeAuthorIDs: [ID!]

excludeIDs: [ID!]

hasPassword: Boolean = false

ids: [ID!]

isSticky: Boolean

metaQuery: [CustomPostMetaQueryInput!]

password: String

search: String

status: [FilterCustomPostStatusEnum!]

tagIDs: [ID!]

tagSlugs: [String!]

}

input PostPaginationInput {

limit: Int

offset: Int

}

input CustomPostSortInput {

by: CustomPostOrderByEnum

order: OrderEnum

}

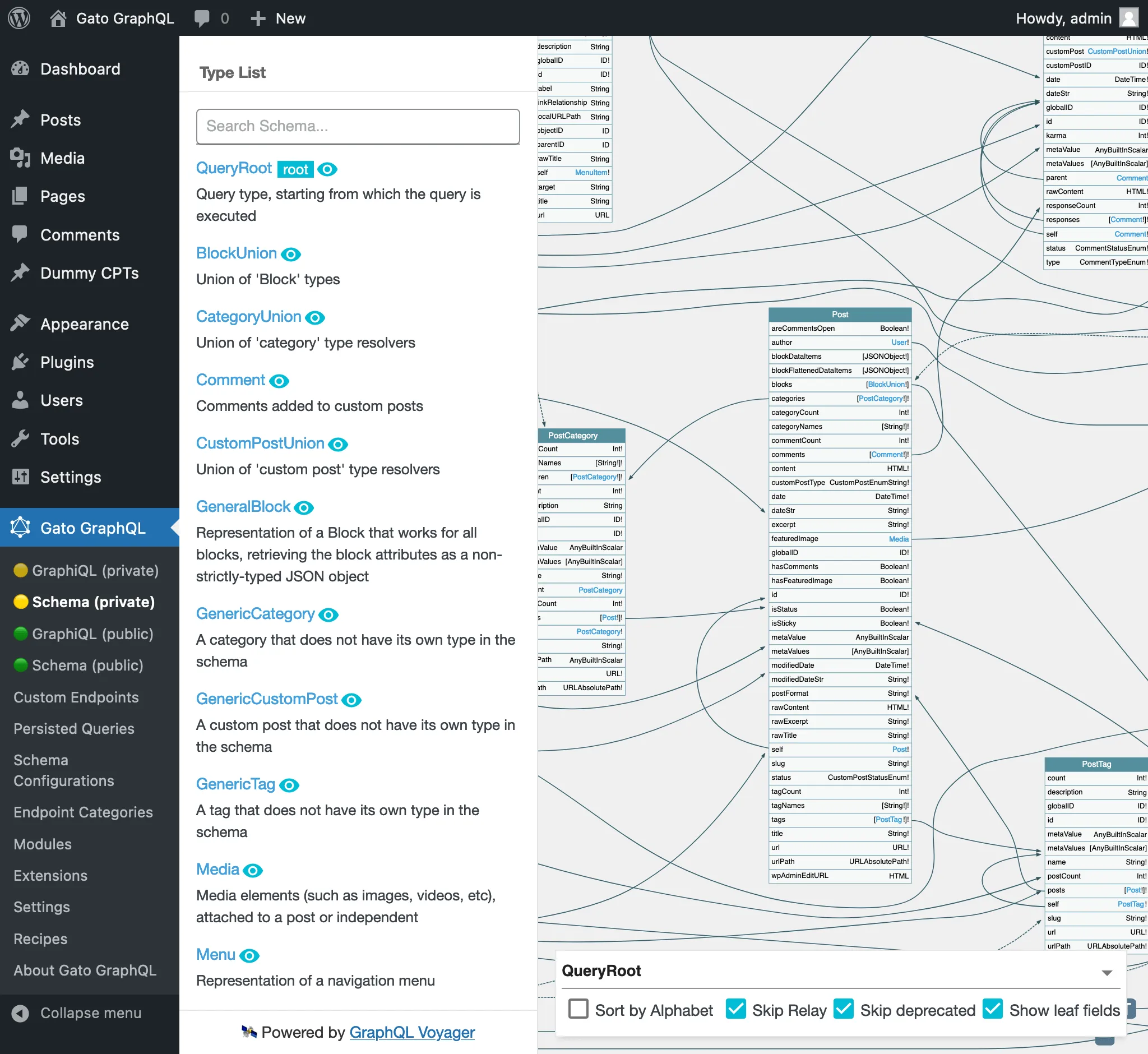

# ...We keep doing this for all entities in the WordPress data model. Once we are done, we'll arrive at the GraphQL schema for WordPress, as visible using the Voyager client (available as "Interactive Schema" on the plugin's menu):

This schema has similarities to the WordPress database diagram, but also several differences. Let's analyse them.

Operations without entity are mapped as Root fields

In the WordPress database diagram represents how data is stored, so there is no "beginning". GraphQL, though, is an interface to retrieve data, hence there must be an initial stage from which to execute the query.

This initial stage is the Root type, or, to be more precise, the QueryRoot and MutationRoot types (to deal with queries and mutations, respectively).

In these two types, we map all operations that do not depend on an entity, such as when executing get_posts(), get_users() or wp_signon():

type QueryRoot {

posts: [Post]!

users: [User]!

}

type MutationRoot {

loginUser(

usernameOrEmail: String!,

password: String!

): User

}The fields do not need to have the same name or signature as the operation they represent. For instance, calling field loginUser can be considered more suitable than signOn.

Grouping schema elements

We can apply enhancements to simplify the schema and make it more useful. For instance, a field can receive all its arguments via an input object, which can be re-used across several fields and makes it easier to visualize the schema:

type MutationRoot {

loginUser(input: LoginUserByInput!): User

}

input LoginUserByInput {

usernameOrEmail: String!,

password: String!

}In addition, the response from a mutation can be a "payload" object, which in addition to returning the affected object can also include the status of the operation and error messages:

type MutationRoot {

loginUser(input: LoginUserByInput!): RootLoginUserMutationPayload!

}

type RootLoginUserMutationPayload {

errors: [RootLoginUserMutationErrorPayloadUnion!]

status: OperationStatusEnum!

user: User

userID: ID

}

union RootLoginUserMutationErrorPayloadUnion = GenericErrorPayload

| InvalidUserEmailErrorPayload

| InvalidUsernameErrorPayload

| PasswordIsIncorrectErrorPayload

| UserIsLoggedInErrorPayloadAll mutations go under MutationRoot

There are operations which do depend on an entity, such as wp_update_post(), which is applied on some post. The corresponding mutation on the GraphQL schema must be added to the MutationRoot type, because that's how GraphQL works.

Then, this operation is mapped like this:

type MutationRoot {

updatePost(input: RootUpdatePostFilterInput!): PostUpdateMutationPayload!

}

input RootUpdatePostFilterInput {

categoryIDs: [ID!]

content: String

featuredImageID: ID

id: ID!

status: CustomPostStatusEnum

tags: [String!]

title: String

}This plugin also supports nested mutations, which are offered as an opt-in feature (because this is not standad GraphQL behavior). Then, mutations can also be added under any type, not just MutationRoot. In this case, we obtain:

type Post {

update(input: PostUpdateFilterInput!): PostUpdateMutationPayload!

}

input PostUpdateFilterInput {

categoryIDs: [ID!]

content: String

featuredImageID: ID

status: CustomPostStatusEnum

tags: [String!]

title: String

}Please notice the difference between inputs RootUpdatePostFilterInput and PostUpdateFilterInput (i.e. between mutations from the root, and nested mutations): the former one has the mandatory property id as to indicate which post to modify, but the latter one does not, as it doesn't need it.

Dealing with custom posts

There is no type inheritance in GraphQL. Hence, we can't have a type CustomPost, and declare that Post and Page extend it.

GraphQL offers two resources to compensate for this lack: interfaces and union types.

For the first one, we create an interface CustomPost for the schema, declaring all the fields expected from a custom post, and we define types Post, Page and GenericCustomPost (to represent all custom post types defined by any installed theme and plugin) to implement the interface:

interface CustomPost {

title: String

content: String

excerpt: String

date(format: String): Date!

}

type Post implements CustomPost {

title: String

content: String

excerpt: String

date(format: String): Date!

}

type Page implements CustomPost {

title: String

content: String

excerpt: String

date(format: String): Date!

}

type GenericCustomPost implements CustomPost {

title: String

content: String

excerpt: String

date(format: String): Date!

}For the second one, we create a CustomPostUnion type for the schema returning all the custom post types:

union CustomPostUnion = Post | Page | GenericCustomPostAnd have fields return this type whenever appropriate:

type QueryRoot {

customPost(id: ID): CustomPostUnion

customPosts: [CustomPostUnion]!

}

type User {

customPosts: [CustomPostUnion]

}

type Comment {

customPost: CustomPostUnion!

}When executing the query, we can either select the fields based on the actual type, such as Post, or on the interface CustomPost:

{

customPosts {

__typename

...on CustomPost {

id

title

slug

status

}

...on Post {

isSticky

postFormat

}

}

}As it can be observed, in the GraphQL schema we need to explicitly assert when we are dealing with posts, and when with custom posts, since they are not the same! Calling these two interchangeably is technical debt from WordPress, which the plugin attempts to fix whenever possible.

For this reason, a custom post is always called CustomPost and not Post, a field dealing with custom posts is always called customPosts and not posts, and a field argument receiving the ID for a custom post is called customPostID and not postID (even though that's how it's called in the mapped WordPress function).

Then, the expectation is always clear:

- Field

User.customPostscan return a list of any custom post, including posts and pages, andUser.postsonly returns posts - Field

Root.setFeaturedImageOnCustomPostcan add a featured image to any custom post, that's why it's not calledsetFeaturedImageOnPost

Not grouping tags (and categories) under a single type

Why is type PostTag (and same for PostCategory) called like that, instead of just Tag?

Because, when executing this query (where a product is a CPT), the results from field tags for posts and products will always be different, non-overlapping:

query {

posts {

tags {

id

name

}

}

products {

tags {

id

name

}

}

}Tags added to posts will not show up when retrieving tags for products, and the other way around (unless a product also uses the post_tag taxonomy, but then it can also be represented with the PostTag type). This does not represent a big deal in WordPress, since these items can be considered different rows from the same database table. But it does matter for GraphQL, which is strongly typed.

Then, it's a good design decision to keep these entities separate, under their own types, and have tags for posts returned under the PostTag type and, if a custom plugin implements its own product CPT, it must use the ProductTag type for its tags.

Giving media items their own identity

Media entities in WordPress are custom post types, only because it was convenient from an implementation point of view. However, the GraphQL schema can avoid this technical debt, and model media elements as a distinct entity, not as custom posts.

This implies the following decisions for the GraphQL schema:

- The

Mediatype does not implement theCustomPostinterface, and won't be part of theCustomPostUniontype - The

Mediatype doesn't have many fields expected from a custom post type, such asexcerpt,dateandstatus. Instead, it only has those fields expected from a media element:

type Media {

id: ID!

src: String!

width: Int

height: Int

}Identifying and mapping enums

In some situations, WordPress uses fixed values from a given set. For instance, the status of a post can only be "publish", "draft", "pending" or "trash".

In GraphQL, we can treat these as enums (instead of strings), and create a corresponding enumeration type. Following the GraphQL standard, enums should be written in uppercase, like this:

enum CUSTOM_POST_STATUS {

PUBLISH

DRAFT

PENDING

TRASH

}However, then the query can't be directly used to interact with WordPress, since executing get_posts( [ "post_status" => "PUBLISH" ] ) doesn't work.

So, as a compromise, we keep these enum values in lowercase:

enum CUSTOM_POST_STATUS {

publish

draft

pending

trash

}Mapping additional types

Blocks are not directly visible in the WordPress database diagram, since they are stored in wp_posts (there is no table wp_blocks), but nevertheless thay are a distinct entity.

Hence, we can still introduce a Block type to map them:

type Post {

blocks: [Block]

}

type Block {

type: String!

attributes: JSONObject

}