Authorization via access control

Authorization is the process of granting access to the different parts and assets of the web application to the users. A common way to authorize users is through access control, in which the admin of the site defines what permissions must be granted to users and other entities in order to access what resources.

Authorization must not be confused with authentication, which is the process of validating that the user is who he or she claims to be, usually accomplished by providing account credentials. Once the user is authenticated, the authorization process must still be performed on every request, to make sure that the user has access to the requested resource.

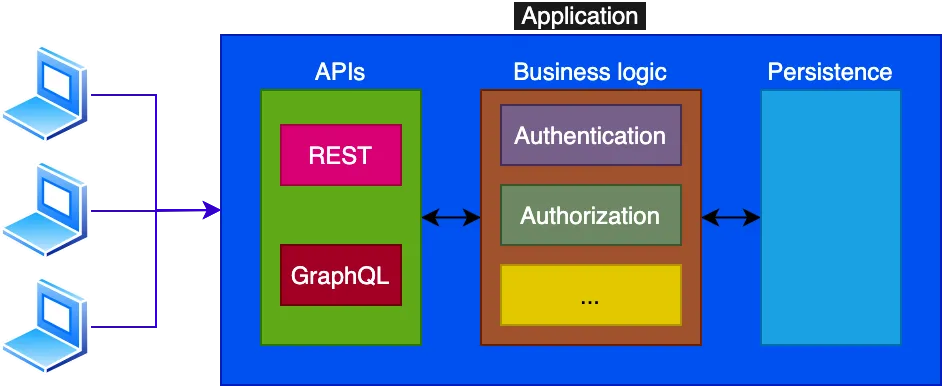

When accessing the application via GraphQL, we must validate if the user has access to the requested elements from the schema. Should the authorization logic be coded within the GraphQL layer?

The answer is no. As the documentation at graphql.org makes clear, the authorization logic belongs to the business logic layer, and from there it is accessed by GraphQL. This way, the application can have a single source of truth for authorization (i.e. the one offered by WordPress):

Gato GraphQL respects this principle, reflecting (and, under the engine, deferring to) the authorization mechanism provided by WordPress.

Access Control Policies

Among the several access control policies we can implement for our application, the two most popular ones are Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) and Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC).

WordPress, and Gato GraphQL, support both of them.

With Role-Based Access Control we grant permissions based on roles, and then assign the roles to the users. For instance, WordPress has an administrator role with access to all resources, and roles editor, author, contributor, and subscriber with restricted permissions in varying degrees, such as being able to create and publish a blog post, just create it, or just read it.

With Attribute-Based Access Control permissions are granted based on metadata that can be assigned to different entities, including users, assets, and environment conditions (such as the time of the day or the IP of the visitor). For instance in WordPress, capability edit_others_posts is used to validate if the user can edit other users' posts.

In general terms, ABAC is preferrable over RBAC because it allows us to configure permissions with fine-grained control, and the permission is unequivocal in its objective.

For instance in WordPress, the editor role has capability edit_others_posts, but we may desire to allow a person with the author role to edit another author's post, yet without granting him or her the whole set of permissions that an editor is granted (such as also deleting other authors' posts). Hence, granting the capability edit_others_posts and checking for this condition is more adequate than checking for role editor.

Defining the Visibility

When the user does not possess the permission to access the requested field from the GraphQL schema, what should the returned error be?

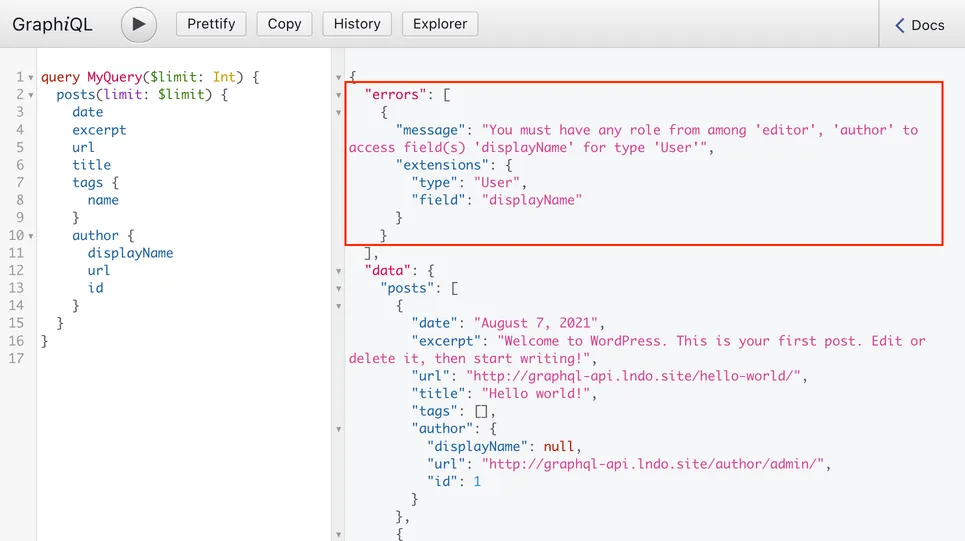

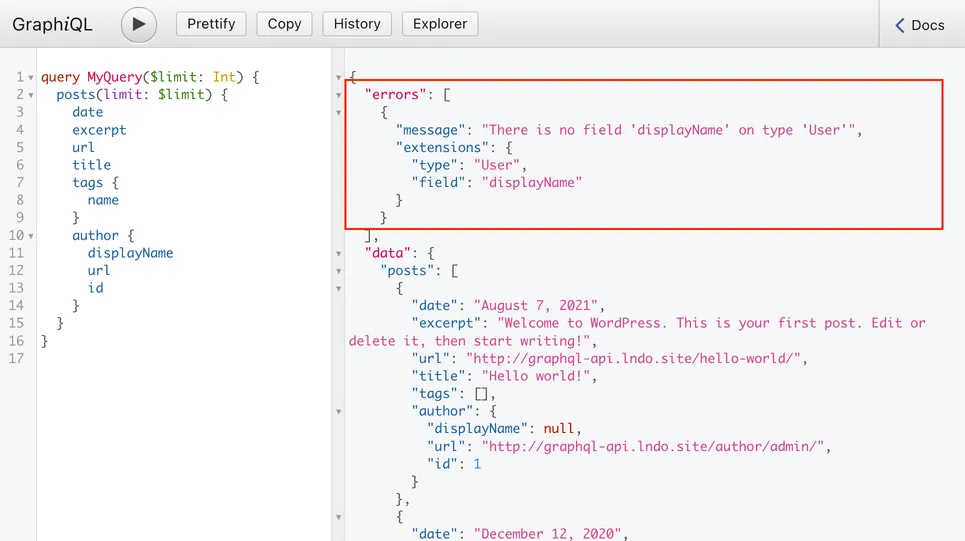

There are two possibilities, in conformity with the desired visibility for the schema: public or private.

For the public schema, the exposed GraphQL schema is the same one for all users, and every field describes what permissions are required to access it. When requesting an inaccessible field, the error message will explain why the user is not granted access.

For the private schema, the GraphQL schema is customized to every user, and only those fields he/she can access will be exposed. When requesting an inaccessible field, the error message will state that the field does not exist.

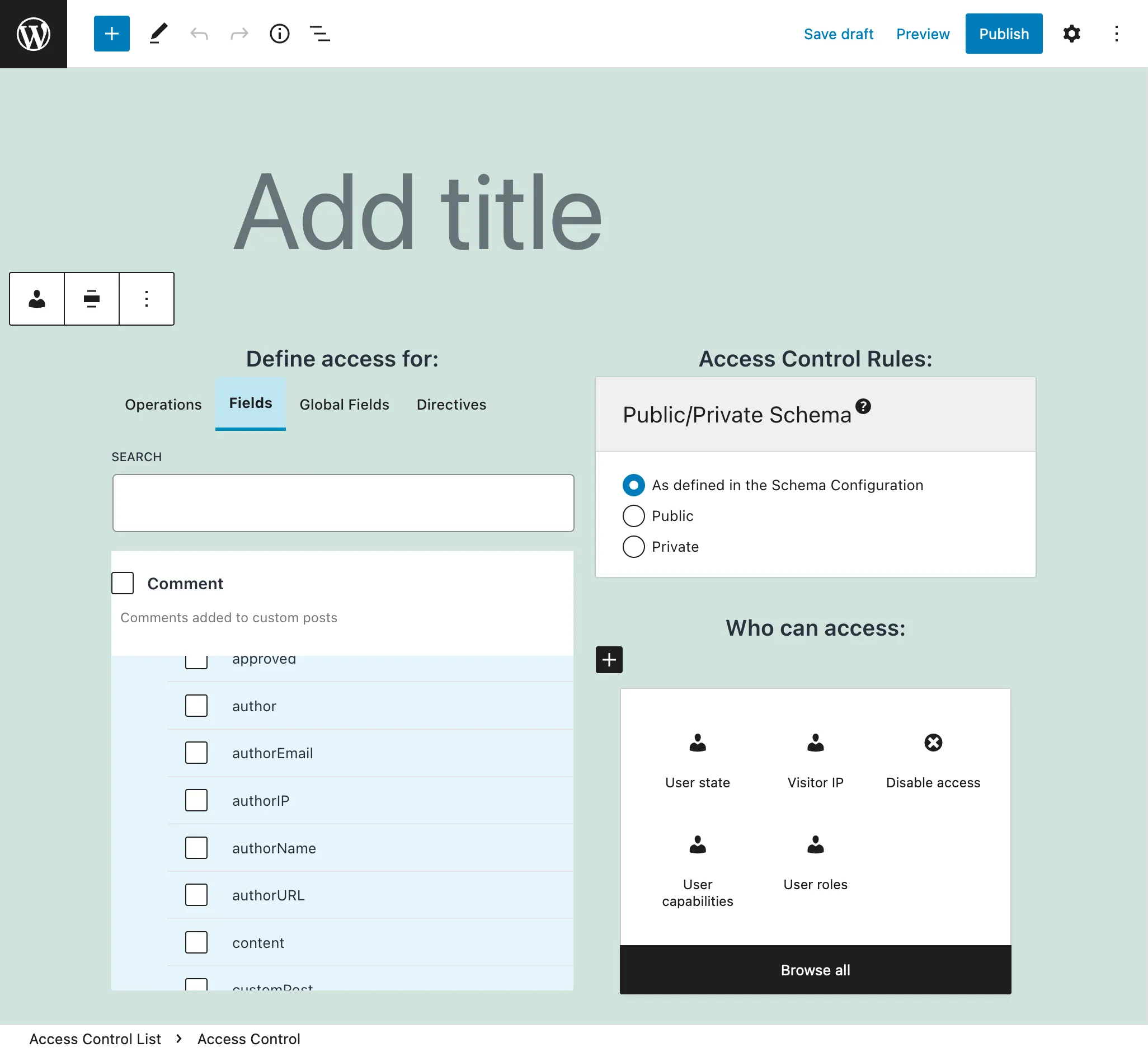

Access Control via the User Interface

In Gato GraphQL, the access control rules are injected into the schema on runtime, as user-defined configuration via access control lists. This way, the GraphQL layer will reflect immediately the changes of access control policy, without the need to update any code or recompile the schema:

The site admin configures the ACL, selecting:

- The fields to validate

- A rule to validate, from among:

- must the user be logged in?

- must the user be logged out?

- must the user have a certain role?

- must the user have a certain capability?

- The rule-specific configuration:

- which roles?

- which capabilities?

- The visibility:

- default (i.e. same one assigned to the schema)?

- public?

- private?