Evolving the schema via field versioning

As the needs from our application evolve, the GraphQL API feeding data to it will need to evolve, too, introducing changes to its schema. Whenever the change is non-breaking, as when adding a new type or field, we can apply it directly without fearing side effects. But when the change is a breaking one, we need to make sure we are not introducing bugs or unexpected behavior in the application.

Breaking changes are those that remove a type, field, or directive, or modify the signature of an already existing field (or directive), such as:

- Renaming a field

- Changing the type of an existing field argument, or making it mandatory

- Adding a new mandatory argument to the field

- Adding non-nullable to the response type of a field

In order to deal with breaking changes, there are two main strategies: versioning and evolution, as implemented by REST and GraphQL, respectively.

REST APIs indicate the version of the API to use either on the endpoint URL (such as https://api.mycompany.com/v1 or https://api-v1.mycompany.com) or through some header (such as Accept-version: v1). Through versioning, breaking changes are added to a new version of the API, and since clients need to explicitly point to the new version of the API, they will be aware of the changes.

GraphQL doesn't dismiss using versioning, but it encourages using evolution. As stated in the GraphQL best practices page:

While there's nothing that prevents a GraphQL service from being versioned just like any other REST API, GraphQL takes a strong opinion on avoiding versioning by providing the tools for the continuous evolution of a GraphQL schema.

Evolution behaves differently in that it is not expected to take place once ever few months, as versioning is. Rather, it’s a continuous process, taking place even daily if needed, which makes it more suitable for rapid iteration. This approach has been laid down by Principled GraphQL, a set of best practices to guide the development of a GraphQL service, in its fifth principle:

5. Use an Agile Approach to Schema Development: The schema should be built incrementally based on actual requirements and evolve smoothly over time

Evolving the schema

Through evolution, fields with breaking changes must go through the following process:

- Re-implement the field using a different name.

- Deprecate the field, requesting clients to use the new field instead.

- Whenever the field is not used anymore by anyone, remove it from the schema.

Let's see an example. Let's say we have a type Account, modeling an account to be a person with a name and a surname through this schema (using GraphQL's SDL - Schema Definition Language):

type Account {

id: Int

name: String!

surname: String!

}In this schema, both the name and surname fields are mandatory (that's the ! symbol added after the type String) since we expect all people to have both a name and a surname.

Eventually, we also allow organizations to open accounts. Organizations, though, do not have a surname, so we must change the signature of the surname field to make it non-mandatory:

type Account {

id: Int

name: String!

surname: String # This has changed

}This is a breaking change because the application is not expecting field surname to return null, so it may not check for this condition, as when executing this JavaScript code:

// This will fail when account.surname is null

const upperCaseSurname = account.surname.toUpperCase();The potential bugs resulting from breaking changes can be avoided by evolving the schema:

- We do not modify the signature of the

surnamefield; instead, we mark it as deprecated, adding a helpful message indicating the name of the field that replaces it - We introduce a new field name

personSurname(oraccountSurname) to the schema

Our Account type now looks like this:

type Account {

id: Int

name: String!

surname: String! @deprecated(reason: "Use `personSurname`")

personSurname: String

}Finally, by collecting logs of the queries from our clients, we can analyze whether they have made the switch to the new field. Whenever we notice that the field surname is no longer used by anyone, we can then remove it from the schema:

type Account {

id: Int

name: String!

personSurname: String

}Issues with evolution

The example described above is very simple, but it already demonstrates a couple of potential problems from evolving the schema:

| Problem | Description |

|---|---|

| Field names become less neat | The first time we name the field, we will possibly find the optimal name for it, such as surname. When we need to replace it, though, we will need to create a different name for it that may be suboptimal (the optimal is already taken!). All possible replacements in the example above have problems:- personName makes explicit that the account is for a person, so if, later on, we must open an account for a non-person with a surname (I don't know... a Martian?), then we will need to evolve the schema again so as to keep consistent names- The "account" bit in accountName is completely redundant since the type is already Account- Otherwise, what other name to use? surname1? surnameNew? Or even worse, surnameV2?As a consequence, the updated schema will be less understandable and more verbose. |

| The schema may accumulate deprecated fields | Deprecating fields is most sensible as a temporary circumstance; eventually, we would really like to remove those fields from the schema to clean it up before they start accumulating. However, there may be clients that don’t revise their queries and still fetch information from the deprecated field. In this case, our schema will slowly but steadily become a kind of field cemetery, accumulating several different fields for the same functionality. |

Let's see how to solve these issues.

Versioning fields

We can create our field with an argument called version, through which we specify which version of the field to use.

In this scenario, we will still have to keep the implementation for the deprecated field, so we are not improving in that concern. However, its contract becomes hidden: the new field can now keep its original name (there is no need to rename it from surname to personSurname), preventing our schema from becoming too verbose.

Please note that this concept of versioning is different than that in REST:

- REST establishes an all-or-nothing situation in which the whole queried API has the same version since the version to use is part of the endpoint

- In this other approach, each field is versioned independently

Hence, we can access different versions for different fields, like this:

query GetPosts {

posts(version: "1.0.0") {

id

title(version: "2.1.1")

url

author {

id

name(version: "1.5.3")

}

}

}Moreover, by relying on semantic versioning, we can use the version constraints to choose the version, following the same rules used by Composer for declaring package dependencies. Then, we rename field argument version to versionConstraint and update the query:

query GetPosts {

posts(versionConstraint: "^1.0") {

id

title(versionConstraint: ">=2.1")

url

author {

id

name(versionConstraint: "~1.5.3")

}

}

}Applying this strategy to our deprecated field surname, we can now tag the deprecated implementation as version "1.0.0" and the new implementation as version "2.0.0" and access both, even on the same query:

query GetSurname {

account(id: 1) {

oldVersion: surname(versionConstraint: "^1.0")

newVersion: surname(versionConstraint: "^2.0")

}

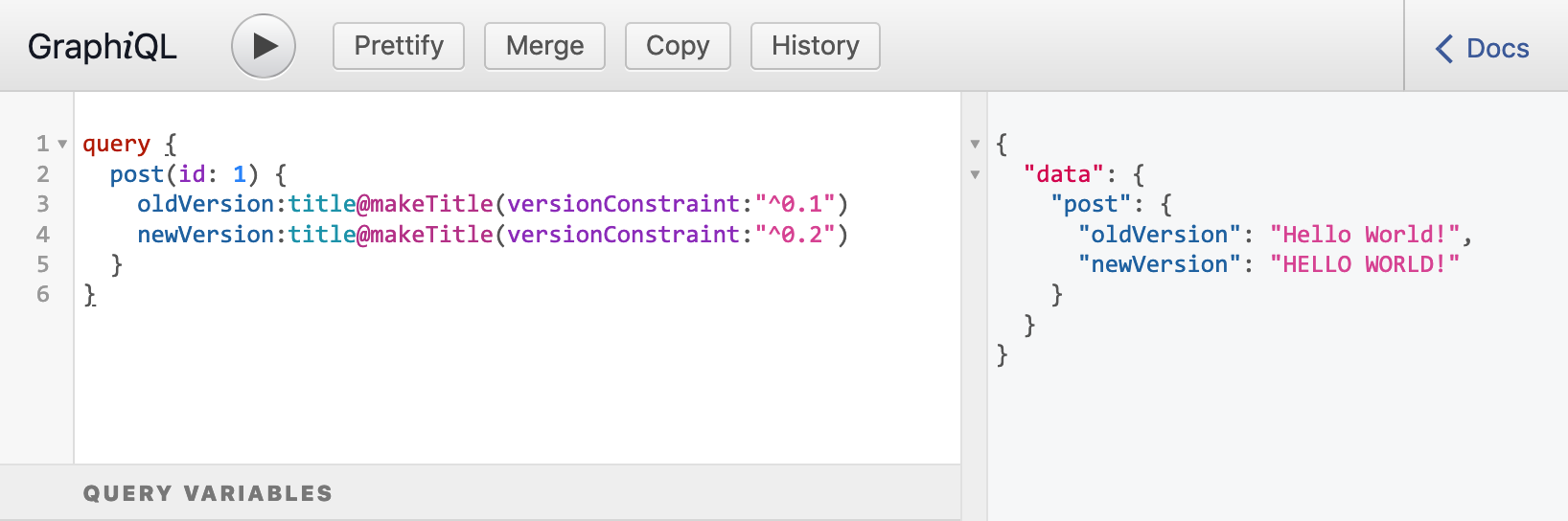

}This feature is available in Gato GraphQL:

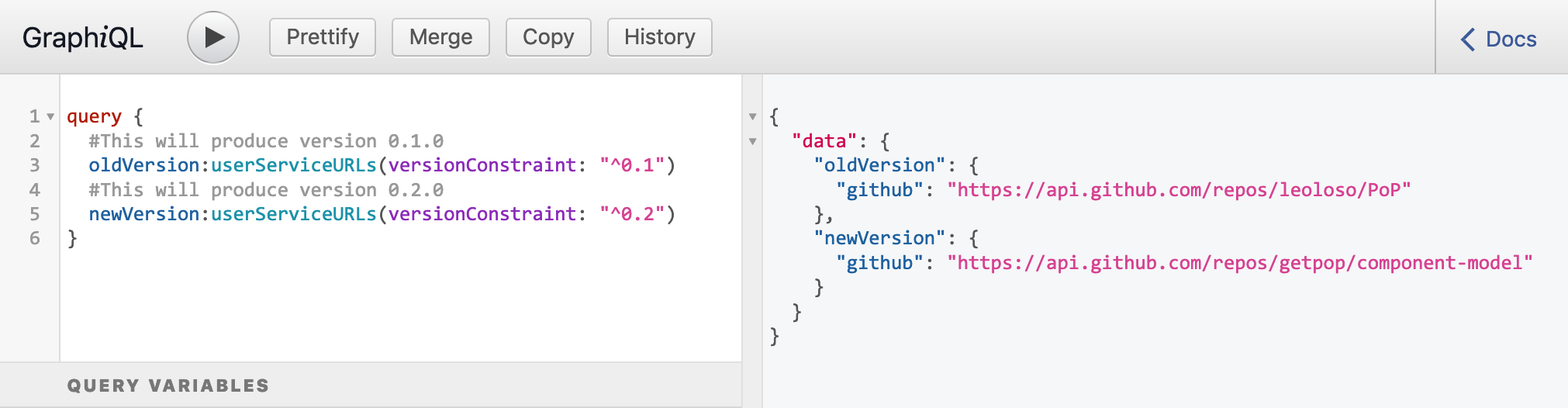

Versioning directives

Since directives also receive arguments, we can implement exactly the same methodology to version directives, too!

For instance, when running this query:

query {

post(by: { id: 1 }) {

oldVersion: title @strTitleCase(versionConstraint: "^0.1")

newVersion: title @strTitleCase(versionConstraint: "^0.2")

}

}It can produce a different response for each version of the directive: